Rise of the Megacity

Today, the world is home to 28 megacities: metropolitan areas with a total population of more than 10 million people. According to the World Economic Forum, it is estimated that, as of 2020, 56.2% of the world population lives in urban settings, a statistic that’s likely to increase to 70% by 2050. Furthermore, 60% of the land that will become urban by 2030 has yet to be built. Humanity is altering the Earth’s geography at an astounding rate – concrete, glass and high rises punctuating the planet’s skylines as anthropogenic markers of infrastructural development. We’re beginning to move on top of one another as a species en masse. The world’s largest buildings now stretch to 160 floors and 3,000 feet. Jeddah Tower, planned as the next tallest structure to date, will stand 180m higher than the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, (828m), climbing over one kilometre into the atmosphere.

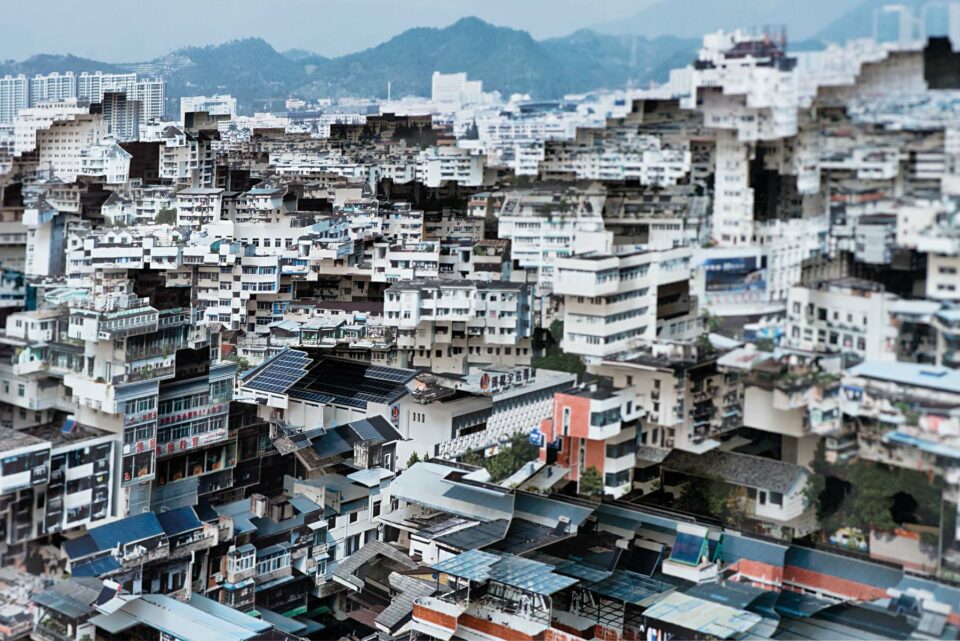

In Michel Lamoller’s (b. 1984) photographic reliefs, various prints are layered on top of one another in ways that mimic our increasingly stacked and urbanised behaviour – each composition representing a new, hyperreal existence in both form and structure. Through the acts of cutting and pasting – and further exaggerating the labyrinthine qualities of megacities – he explores what it means to exist in radically mechanised landscapes, whilst questioning the ultimate reality presented by images today. Lamoller speaks to us in light of a new show at The Ravestijn Gallery, Amsterdam, Anthropogenic Mass.

A: What’s your earliest experience with photography?

ML: My father was a trained repro-photographer. He had a darkroom in the house and taught me how to develop black-and-white prints. After a photo trip to Paris at the age of 18, I was completely hooked. I will never forget the magic of seeing the print appear in the developer. Then, after high school, I had the opportunity to do an internship at Magnum Photos in New York, where I met the likes of Alec Soth and Bruce Gilden. Whilst I was there, I was advised to build a portfolio, which helped me to get into the Academy of Fine Arts Hamburg. After studying, I began to feel limited by the classical approach to photography, and I was tired of spending so much time with Photoshop. I wanted new forms of expression, so I started to play a lot – starting with vintage postcards, then quickly moving onto my own images. Since then, my working process has continuously developed, and I now have a range of stratified postcards several metres in size.

A: What does the term “anthropogenic” mean to you?

ML: For me, the term is key when it comes to describing the condition of the planet in this geological epoch. It helps me to sharpen my perception and to rethink what we mean when we discuss the concepts of “nature”, “landscape” or “environment.” We are in midst of a learning process. We have to transform rational, abstract knowledge about the climate crisis into an inner condition of real feelings that will, ideally, lead us to action. Images help us to do this. Some outstanding photographers have dedicated them- selves to a similar task, such as the Canadian Edward Burtynsky, whose works are an example of how pictures can create awareness. Paradoxically, though, photographers jet around the world for the “good cause” – leaving behind an above-average CO2 footprint. We are still part of the problem. Anthropogenic Mass is part of my reflection or contribution to this conversation – visualising a literal manmade concretion.

A: What version of the Anthropocene are you document- ing? Is this a representation of the present as it exists today, or perhaps a vision of a future yet to be built?

ML: I use photos that represent the “Great Acceleration”: an era of economic growth and global burning of resources, an exponential curve from the mid-20th century up to today. I produce documentary photos in the sense that the places are real – and haven’t been manipulated by digital image editing. However, the final works have a fictional nature to them: they show an altered reality, with just a touch of decadence. Being artworks, they are open to interpretation, of course: they can be read as utopias or dystopias – or per- haps they are simply deconstructions of a universal urbanity.

A: How does each composition begin and end?

ML: Initially, I take a photo and do basic digital image pro- cessing on the result. I then print that particular image sev- eral times and attach each of these to a paperboard. Afterwards, I start cutting away parts of each layer with a scalpel and add space holders between the gaps. This process can take months, depending on the size and complexity of the work. Eventually, the stratified images get accurately framed.

A: Generation Y (1981-1996) was the last group to have grown up in an analogue world, before experiencing dig- ital adulthood. From Generation Z (1997-2012) onwards, newborns are being introduced to the planet as digital natives, where technology is ubiquitous and intuitive. Why do you choose to work with both media, and what does this mean in our current age of image proliferation? ML: Through my father, I grew up with analogue photography, which, for me, contained magical qualities: something warm and emotional. The moment I first held a digital camera in my hand, all of those feelings disappeared, and the significance was lost. Later, social media came along and accelerated the devaluation of images even further. By subjecting photos to sculpture, spending whole weeks with a single motif, I try to give the image back its magic, or to quote Walter Benjamin: “the aura to make it unique again.”

A: In what ways are you exaggerating the process of architectural infrastructure to mimic its rapid speed? Can the creation of an artwork be relative to its subject?

ML: Through a depth of the layers and resulting density, I create an almost philosophical discourse on human development, achieved through the concept of urban space. The architectonic infrastructure, as depicted in my works, may seem exaggerated in a surreal way, but in fact, I have merely constructed an approximation of the actual scale of human encroachment on nature: in its speed but also in its mass.

A: Today, reality is constantly being questioned. How far are you considering the possibilities of photography to further obscure or reveal? Can we “enter” into an image?

ML: Interestingly, photography is, more often than not, accepted as a “proper” representation of reality. I don’t see it that way at all. To me, photos are constructions of one aspect of reality. In that sense, they reveal and obscure at the same time. Taken out of context and seen for what it is, a picture leaves more questions than it does answers. Can we enter an image? The question implies we are standing “outside” of an image in the first place. Being visual creatures, we innately create an inner model of the world in our imagination. Hence, we’ve never left the initial image in which we already live.

A: Are there certain locations that you return to?

ML: I took most of the images in Chinese megacities, such as Shanghai and Hangzhou. Shanghai, especially, had a really big impact on me because I could clearly sense the speed of its urbanisation. Arriving there from wintry Berlin it felt like I was landing in the future. To me, the megacities are not only visual adventures but symbols of our world and new modes of living, in which the human being is the absolute: the central point of reference. Metropolitan spaces are a blueprint for our self-contemplation and anthropocentric behaviour. One of my favourite pieces is a large-scale Osaka cityscape. I love it because it challenges the viewer’s perception. The original, unedited photo was shot from an elevated position and shows the incredible density of visual information. On the other hand, the overkill of the photo relief makes you feel this exact density in a spatial context.

A: Should artists be representing the world as it is, or offer- ing something altogether new for it to be considered “art”?

ML: Art is never a representation but always a construction. When a person makes a statement or an image, it first of all represents the point of view of that particular individual, and not a fact about reality or a certain state of being. Art, therefore, is a system of symbols and should be treated as such.

A: Do you see your works as images or objects? Can the two be divisible, or is there no essential difference?

ML: They are bas-reliefs; their three-dimensional character is very important, but the cut-out shapes don’t resemble anything. If the photo faded away, there would be no recognisable shape left in its place. In that sense, every work is an indivisible symbiosis of object and image. Being (almost) three-dimensional, my pieces can’t be photographed satisfyingly and have to be seen in person, in real life. Given that a big part of life has moved into the digital sphere, I like the idea that some things still can’t be consumed or understood whilst sitting at home on the couch. We need physical experiences; we have to get up and go to the gallery or museum.

A: These images seem to exist in the same realm as Michael Wolf’s Architecture of Density, or Andreas Gursky’s montage typologies. Who, or what, are you inspired by?

ML: For me, the worst reason to make an artwork is responding to another artwork. I am familiar, of course, with my respected colleagues, and their images are certainly part of my picture library. If I were to pin down an external influence, however, it would be the 1975 show New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape (the International Museum of Photography, George Eastman Museum, Rochester.) However, critical texts about the Anthropocene, increasing ecological issues and dwindling biodiversity have been far more influential to my latest body of work. In 2021, for example, the Weizmann Institute of Science, Israel, found that all manmade things have now gained the same weight as the Earth’s biomass. This was a huge turning point, and it has become a striking metaphor for our interrelation with the planet.

Words: Kate Simpson

Anthropogenic Mass, The Ravestijn Gallery, Amsterdam/ 30 April – 11 June

Image Credits:

1. Michel Lamoller, Anthropogenic Mass 2 (2021). 7 layers of Archival Inkjet Print: 60cm x 40 cm x 10 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

2. Michel Lamoller, Layerscape (passive ingression) (2020). C-Prints: 20cm x 30cm x 8cm. Courtesy of the artist.

3. Michel Lamoller, Layerscape (Subway 4) (2021). 10 layers of c-prints: 20cm x 30cm x10cm. Courtesy of the artist.

4. Michel Lamoller, Anthropogenic Mass 3/ Acity 6 (2021). 9 layers of Archival Pigment Prints: 40cm x 60cm x 15cm. Courtesy of the artist.

5. Michel Lamoller, Anthropogenic Mass 1 (2021). 9 layers of Archival Pigment Prints: 65cm x 100cm x 15cm. Courtesy of the artist.

The post Rise of the Megacity appeared first on Aesthetica Magazine.

from Art Life Culture https://ift.tt/Qp06qvl

via IFTTT

Comments

Post a Comment